2. Three information-organizing approaches I do not use for academic research

I don’t use these information-organizing approaches, but you might want to.

The video directing people to this post can be found on YouTube here.

Introduction

Welcome back, my fellow intermediate users of Obsidian. If you don't know why I'm referring to you as an "intermediate user of Obsidian," check out this video.

In that video, I talked about coming up with key questions to guide and give some order to whatever development of ideas you're interested in doing. I pointed out that one advantage of coming up with and then trying to answer those questions is that your Obsidian vault (or Logseq graph or whatever the name of the database is in the app you're using) is "less likely [to become] a mere dumping ground for everything you consume." You're less likely, in other words, to fall victim to what has been called the Collector's Fallacy, which is the mistaken belief that the more information you collect, the more knowledgeable you will become.

However, if you're interested in developing ideas, you can't (or probably shouldn't) avoid collecting information altogether. And if you're going to collect information, you need to give some thought to how you're going to organize it because otherwise your vault will become repulsive (in the sense that you won't ever want to open and do work within it).

There are 1,786 different ways of organizing information in Obsidian and similar apps. That number's a guess, but just know it's a very large number, as one quickly learns when experimenting with backlinks, transclusions/embeds, queries, tags, metadata, templates and—if you're using Obsidian—multiple community plug-ins (e.g., Dataview, Excalidraw, Excalibrain, to name but a few). There are so many different ways of organizing information in an app like Obsidian that it took me at least two years to finally settle on an approach that I find at least 80% satisfying (if experiencing intellectual paralysis is your thing, aim for an approach that's 95–100% satisfying).

What this post is about

In this post, I will lay out three ways of organizing information. More specifically, I will present three ways of using key-question pages to organize relevant information. Those three ways are as follows:

- Add relevant information directly to a key-question page (useful when you have a project deadline to meet in the near future and/or you're certain you will use the information in the future). Note: what I call a "page" is what Obsidian calls a "note." A page or note is a Markdown file in an Obsidian vault.

- "Tag" relevant information with a key-question page so that the information shows up in the backlinks of the key-question page (useful when you can work at a more leisurely pace and/or when you're collecting material you want to review before deciding whether to use it).

- Use a combination of #1 and #2.

None of these ways are ones I use. So why learn about them? For three reasons:

- Although they do not work for my purposes, they might work for yours (or although they might not work for all of your purposes, they might work for some).

- In order to properly understand why I have adopted a different approach, it helps to see the problems with these first three approaches that my favored approach was designed to overcome (in a future post—but not the next one—I will describe the approach I now use, which, by the way, relies primarily on what I call claim pages, not the key-question pages discussed in this post).

- By (a) presenting you with approaches that I do not use and (b) waiting to disclose the approach I currently use, I place you in the position of having to think for yourself about an approach that would suit your needs. (If you're reading this post sometime after the summer of 2023, you probably don't have to wait to see the post that lays out my current approach, but perhaps you should wait nevertheless since thinking for yourself is a good thing, even though often frustrating).

IOA #1

The first information-organization approach (IOA #1) is this:

It was an approach kind of like this one that I used during the Dark Ages of writing my dissertation (that period was technologically dark—well over a decade before the advent of Roam, Obsidian, Logseq, and similar apps—and, for me and plenty of other people in graduate school, also mentally or spiritually dark). For each chapter of my dissertation, I had a single Microsoft Word document titled “notesTHEMATIC,” where I would list all the main questions I wanted to answer as well as all the main points I wanted to make. Whenever I came across relevant material in a text I was reading, I’d scroll through the Word document till I found the question or point it related to, and then I’d add it there. I guess there were worse ways I could have done things, such as using finger paint to take all my notes.

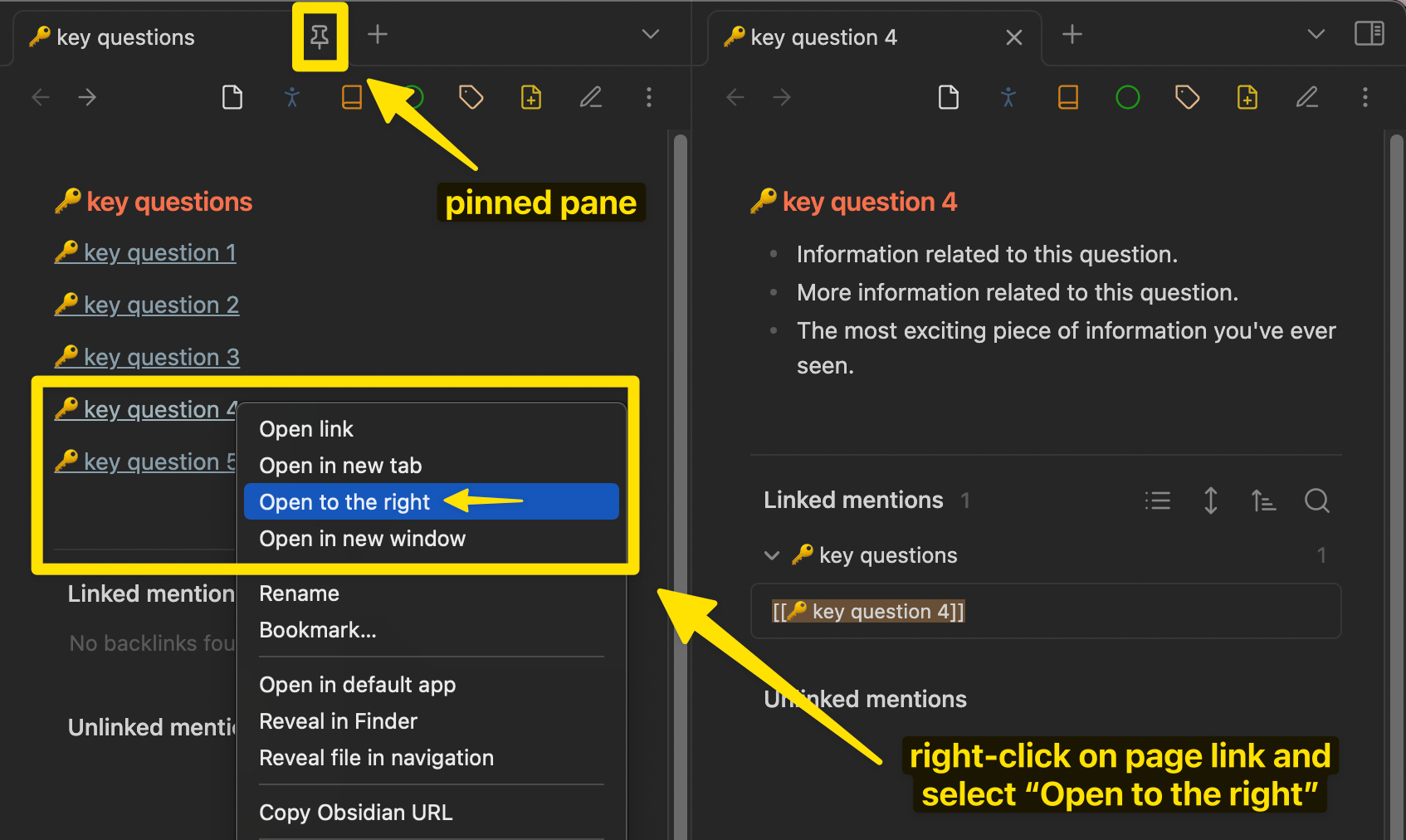

With Obsidian, you could adopt something like this approach but make it a lot smoother.

(a) For instance, when reading, watching, or listening to something, you could have open in Obsidian a pinned pane containing links to all your key questions, and then when you come across something you want to add to one of those, you could click on maybe just a link or two to get to the page you want and add the material directly to the page.

Doing things this way might work for some of you, depending on what your purposes are.

(b) Alternatively, if you don’t want to do a bunch of clicking on links, you could use a keyboard shortcut to call up the Quick Switcher (an Obsidian core plug-in), type usually just a few letters to call up the particular note you want, and then add the material to the page.

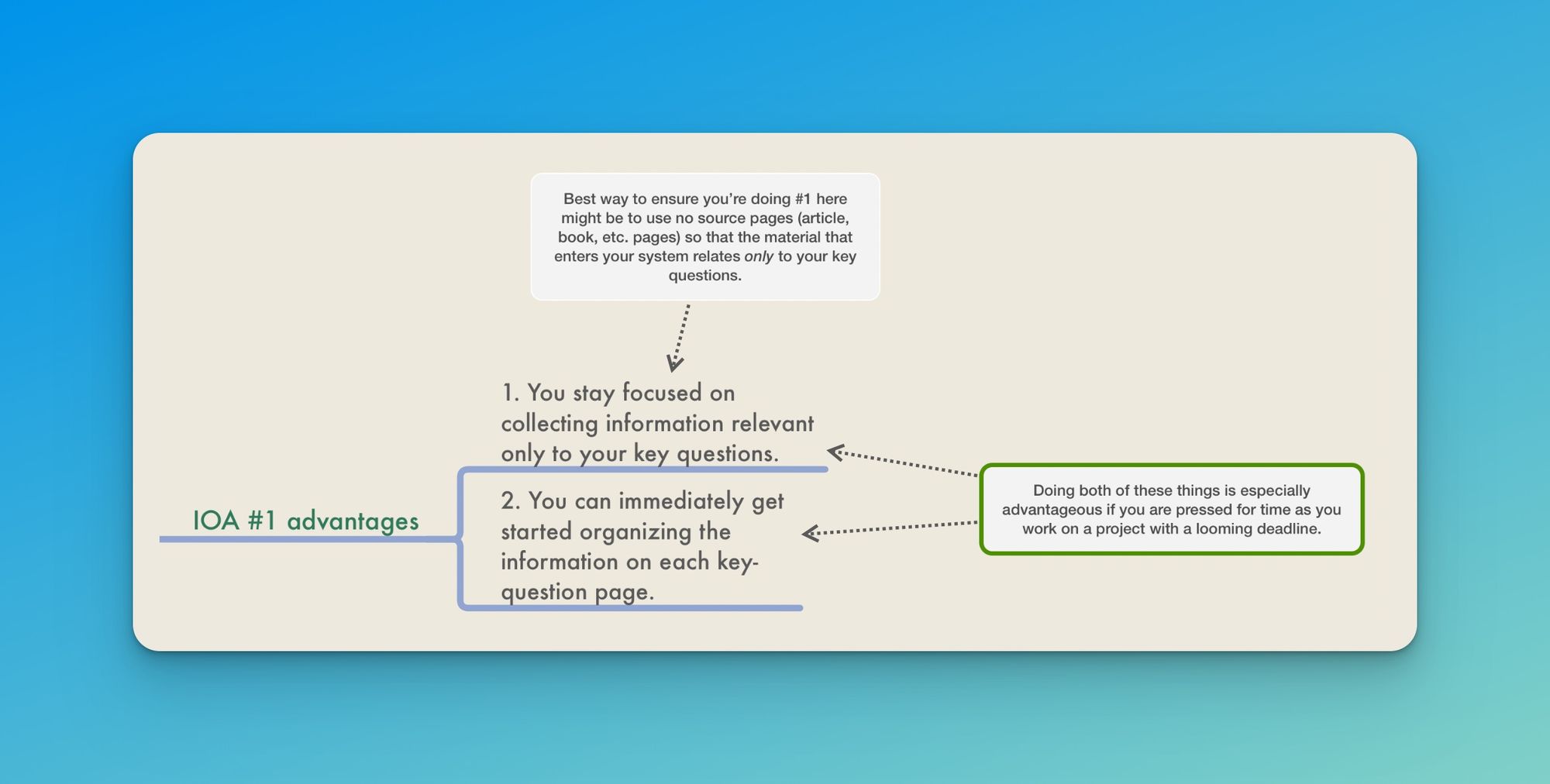

Advantages of IOA #1

- One advantage of adopting an approach like this is that you remain focused on answering your key questions rather than succumbing to the temptation to take notes on everything in a book that you find interesting (or on everything that Tiago Forte and others would say “resonates” with you).

- A second advantage of this approach is that you can immediately get started organizing information on the key-question page. If instead all relevant information were accessible only via backlinks on the key-question page, that information would likely remain unorganized until some future point when you click on the backlinks and review the information those links take you to (note: this wouldn't necessarily be a bad thing—for some, that might be preferable, and it's what IOA #2 is for).

When to use IOA #1

If you have a project deadline you need to meet rather soon (let's say "rather soon" means "sometime in the next 4–6 weeks") and thus need to be laser-focused on answering certain questions and organizing your ideas in order to meet that deadline, IOA #1 might be a good approach to adopt. (What's a "project"? My own projects are usually writing projects, but a project could also involve creating a video, producing a podcast episode, preparing for a presentation, choreographing a dance piece that expresses the movement of ideas in Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit, etc.)

IOA #2

The second information-organizing approach (IOA #2) is this:

There are two terms I need to define here.

- First, a source page in my Obsidian vault is a page containing quotations and other information from a book, article, podcast episode, video, lecture, etc.

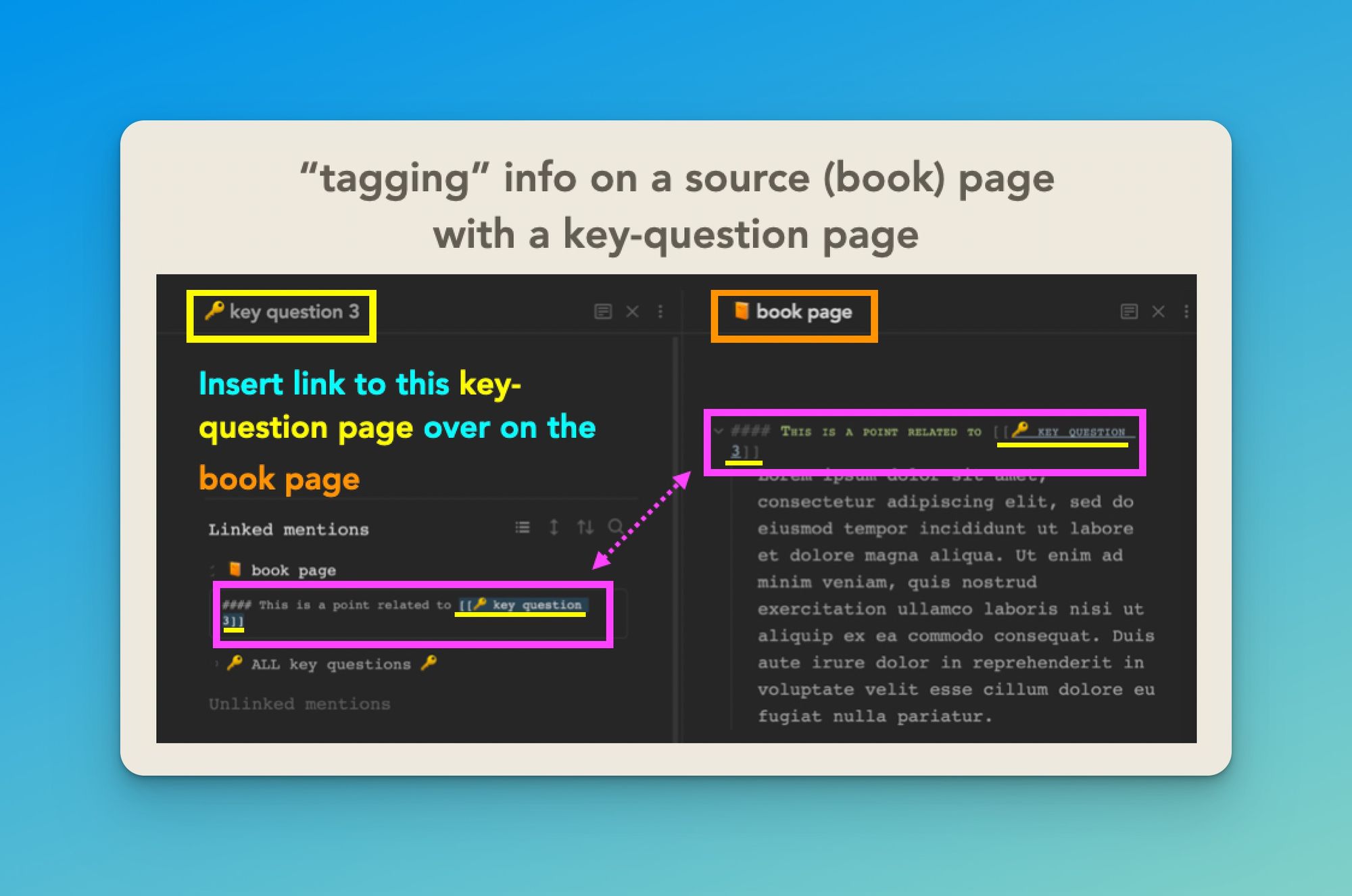

- Second, when I talk about using a key-question page to tag material on source pages that is relevant to a key question, I'm not referring to what Obsidian and other apps call tags. To create regular tags in such apps, you would use a hashtag (e.g., #menstruation or #necrotic_changes_of_uterine_mucosa). When I speak of using key-question pages to tag material, I’m saying that when you have on a source page some material relevant to a particular question, you could then, right next to that material, type double square brackets, start typing the name of the relevant question page, and then select the page you want when it pops up. (If you're interested, check out what Curtis McHale says here about "tagnotes," which for him—and me—serve as "collection points," though I prefer the term "tag pages" for reasons no one would probably care to know. You might also want to look at what Bryan Jenks says here about he uses page links as tags.)

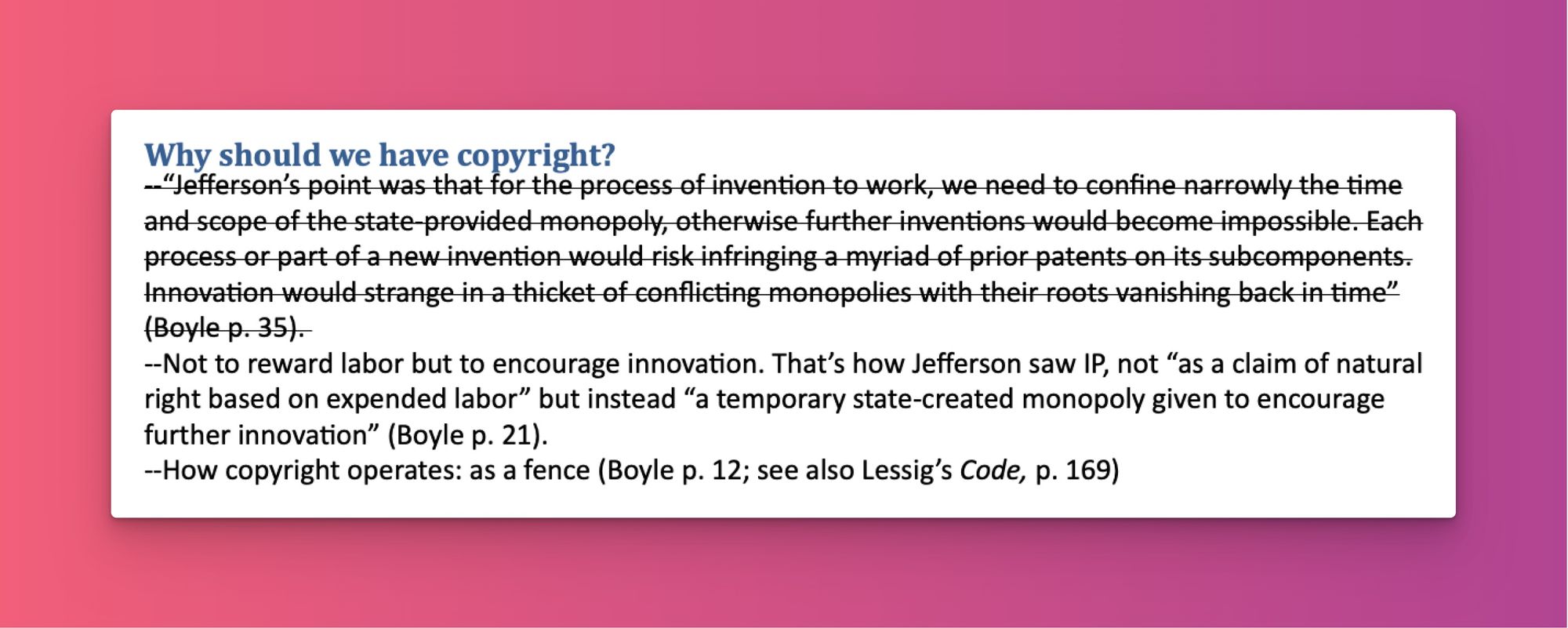

When you use a key-question page to "tag" material on a source page, that material (or at least a portion of it) will show up in the backlinks (or "Linked mentions") section of the key-question page, as you can see in the image below. Contrary to IOA #1, where you would add material directly to a key-question page and (maybe) immediately start organizing that material, with IOA #2, you would likely tag a fair amount of material with a particular key-question page and then set aside time to review that material when it comes time to write up an answer to the key question (which you might do so as to produce what Tiago Forte calls an "intermediate packet," a term that is explained by Forte here and by Ramses Oudt here) or to use in a project the material you've collected by connecting it to the page for that key question.

Three things about this image:

- Of course, contrary to what the image above might suggest, you wouldn't need to have the [[🔑 key question 3]] page open in order to tag material on a source page that's relevant to that key question (even a beginner Obsidian user knows that).

- What you see in the pink rectangle on the right isn't what I would write on a source page. Instead of writing, "This is a point related to [[🔑 key question 3]]," I would write a brief statement that (a) summarizes the quotation under it and/or (b) indicates what the point is in the quotation that has caused me to take the time to add the quotation to a source page in my Obsidian vault. I often refer to such a statement as a "description" of the quotation it precedes.

- I place four hashtags at the front of each "description" to create a Level 4 heading. (a) Why include a heading at all? In cases when I want to transclude (or embed) on another page not just the description of a quotation but also the quotation itself, I can transclude both by transcluding just the heading. (b) Why a Level 4 heading? On my source pages, I have a section titled "Highlights and notes," which is a Level 1 heading. For each chapter of book within that section, I have a Level 2 heading consisting of the chapter number and title. Every once in a while, I will include titles of chapter sections too—that's what the Level 3 heading is for (usually). Of course, some chapters have not only sections but also subsections, so why not use Level 4 and perhaps also Level 5 for those and use Level 6 for descriptions? You could do that, but I've never found it important to include in my source pages an exhaustive list of section and subsection titles, so Level 4 is what I use for descriptions.

Advantages of IOA #2

The advantages of IOA #2 are best understood when presented as solutions to problems with IOA #1, which I will be discussing in my next post.

When to use IOA #2

If you have a project deadline many weeks, several months, or even a couple of years from now, you might want to use something like IOA #2. The same might be the case if you have no project deadlines you need to meet but (a) nonetheless might want to complete some projects in the future and/or (b) simply enjoy developing ideas. I say "something like IOA #2" because the approach I currently use is like IOA #2 but better (as noted earlier, I will lay out my current approach in a future post, an approach that relies primarily on claim pages, not key-question pages).

IOA #3

The third information-organizing approach (IOA #3) is a combination of IOA #1 and IOA #2:

When to use IOA #1 (as part of IOA #3)

Using IOA #1 as part of IOA #3, you might place directly on a key-question page only what you are more or less certain you will include in whatever project for which you decided to create that key-question page. What you place directly on a key-question page could be an apt quotation, some key numerical data, an important diagram, a breathtakingly beautiful (or disturbing) photo, an audio clip, a link that takes you to just the right spot in the middle of a YouTube video, and so on.

One thing to keep in mind here is that when you first encounter material relevant to a particular question page, you might be inclined to think—perhaps because of the newness of the information—that it’s definitely something you will want to use later.

Therefore, if you adopt this first approach and find yourself placing directly on the key-question pages lots and lots of information, you might need to exercise some restraint. One way you might do that is to use IOA #2 more frequently.

When to use IOA #2 (as part of IOA #3)

You can use IOA #2 as part of IOA #3 when you want to link to a key-question page material that you are fairly certain you will want to review if and when it comes time to write about or do something with the information relevant to the key question.

In other words, if the material rises above the threshold of “I’m going to want to review this in the future” but doesn’t jump out as being something you're pretty much certain you will use in the future, then that material can be tagged with a key-question page. When it gets tagged with, or linked to, a key-question page, it shows up in the backlinks section along with everything else linked to the key-question page.

As is the case with using IOA #1 as part of IOA #3, when using IOA #2 as part of IOA #3, you might find that you need to exercise some restraint. When people see for the first time how easy it is to tag material with a key-question page—simply type some square brackets, type a few letters, and hit return—the temptation is to over-tag.

My advice is that you not tag something with a key-question page (or with a claim page, as I will discuss in a future post) simply because it’s in some way relevant to that question. Unless your aim is to come up with a list of absolutely everything that is in some, even remote, way related to a particular question, then whenever you come across relevant material, make sure to step back and ask, "Is this something (a) merely relevant to a key question OR is it something that (b) is both relevant and I am pretty sure I will want to review in the future as I consider material to make use for a project?"

Advantages of IOA #3

One advantage of adopting IOA #3—that is, a combination of IOA #1 and IOA #2—is that doing so gives you a way of distinguishing between different levels of relevance for the material that you collect. Material that you decide is of the highest relevance is placed directly on a key-question page, and material that is apparently of less relevance appears in the backlinks section of that same page (the actual relevance of the latter is something you would determine later, when reviewing the linked-to material, during which time you might also find that material you had placed directly on the key-question page isn't actually of the highest relevance—such is life).

With the information you’ve collected being separated based on relevance, it should be easier for you to write out answers to your key questions or figure out what material to use in a project since you can focus primarily on the material you have identified as being of the highest relevance. In plenty of cases, that will be the only material you need to look at, but for those times when you want to look at yet more relevant material, you can turn to the backlinks sections of your key-question pages.

The backlinks section kind of sucks

However, as any intermediate user of Obsidian probably knows, combing through information in the backlinks section can be a frustrating experience if you have too much material linked to in that section. The approach I currently use was designed to eliminate that frustration, but frustratingly for you perhaps, I'm going to wait a little while to lay out that approach.

In the meantime, give some thought to what information-organization approach you think might work for you. If you want to share your thoughts with others or have questions you'd like answers to, use the Comments section below (this is the first time I've activated the Comments section, so behave).

This piece was also published on Medium. Click here to see it there.